doors <- c(1,2,3)Solving the Monty Hall problem with R

The Monty Hall problem is a statistical puzzle based on an American game show. Because I have zero trust in myself when it comes to paraphrasing it correctly, here’s the Wikipedia version:

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

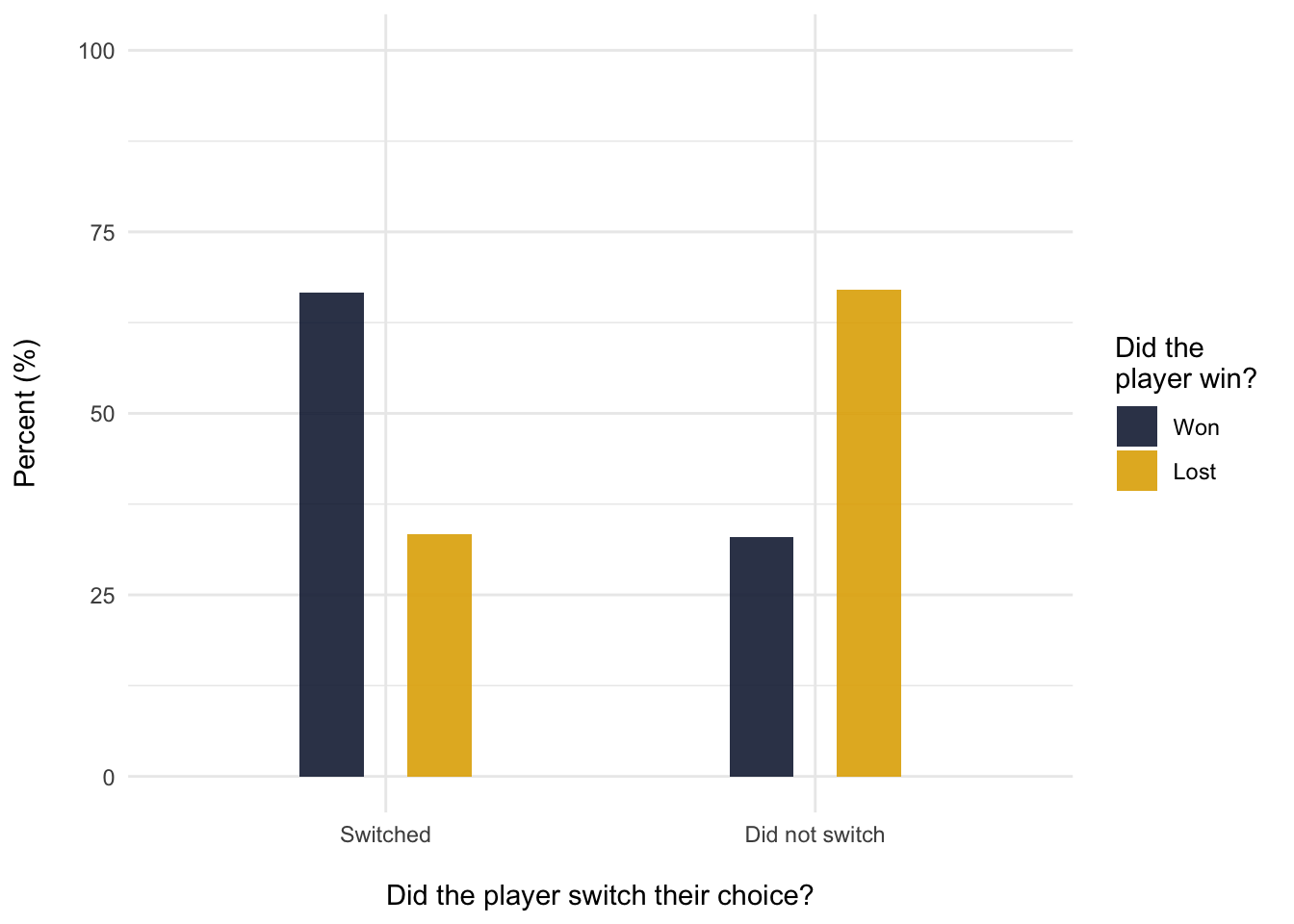

What makes the puzzle fun is the fact that the solution goes completely against intuition. At the point of switching, the probability of winning is 50/50 (there is one winning door and one losing door that you can switch to), but the real probability of winning is 2/3rds if you switch your choice and 1/3rd if you don’t. Once you know the why of the answer, you can feel very smug and wow everyone around you with your out-of-this-world knowledge when the opportunity finally presents itself1.

General solution

To get the real probability of winning conditional on whether or not we switch our choice, we need to consider the whole sequence of events from our original choice until we switch (instead of just considering the probability at the point of switching).

There are more clever ways of working this out with formulas, but, alas, this is not a post written by a clever person. My go-to, if I ever need to explain the solution to someone else2, is to write out all the possible sequences of events for a single round. Let’s say that door number 2 is the winning door. The crucial detail to remember is that the host knows where the car is and will always open a losing door (assuming that we want to win the car, not the goat). In this case, the following sequences of events can occur:

We have 2 wins and 1 loss if we switch, and 1 win and 2 losses if we keep the same door. Switching the door is therefore to our advantage. Now let’s simulate this in R to see if it’s really true over thousands of trials.

Simulating the Monty Hall with R

To simulate Monty Hall trials, we’ll mostly need functions sample() and setdiff() from base R, with some ifelse statements and a loop thrown into the mix. Start by creating a vector that represents the three doors:

Next, set up the winning door and the player’s choice by sampling from the doors object:

set.seed(99) # set seed for reproducibility

winning_door <- sample(doors, 1)

players_original_choice <- sample(doors, 1)For this round, the winning door is 1 and the player has selected the door number 2. You can check this by entering the winning_door and the players_original_choice objects into the console. The losing doors are then the doors object without the winning door:

losing_doors <- setdiff(doors, winning_door)Now we need to figure out which doors is the host going to open. If the player’s original choice is the winning door, then the host picks one of the losing doors. Otherwise they pick one of the losing doors that isn’t the player’s original choice:

door_open <- ifelse(players_original_choice == winning_door,

sample(losing_doors, 1),

setdiff(losing_doors, players_original_choice)) Now let’s decide whether the player is going to switch. For this round, I’m assigning the value TRUE (i.e., they are going to switch), but we’ll loop over different values once we put all of the code together. We can now get the value for player’s final choice: if they switch, their final choice will be whichever door is left when we remove the door that was opened by the host, and the door that the player originally selected. Otherwise (if they don’t switch), their final choice will be their original choice.

does_player_switch <- TRUE

players_final_choice <- ifelse(does_player_switch,

setdiff(doors, c(door_open, players_original_choice)),

players_original_choice)So, they first select door 2, the host opens door 3, the player switches to 1. Do they win?

players_final_choice == winning_door[1] TRUEHappy days. Now let’s repeat this process a few thousand times, alternating the values for whether or not the player switches their choice. I’m going to set up 3 additional objects before we wrap everything in loop:

n_iter <- 1000

switch_choice <- rep(c(TRUE, FALSE), each = n_iter/2)

monty_df = NULLn_iteris the number of iterations we want to complete in the loopswitch_choiceis a vector of TRUE and FALSE values that we’ll be iterating over. Each should be repeated 1000 / 2 times.monty_dfis an empty object. We’re going to save values into this object at the end of each iteration.

Set up the loop:

for (i in switch_choice) {

winning_door <- sample(doors, 1)

players_original_choice <- sample(doors, 1)

losing_doors <- setdiff(doors, winning_door)

door_open <- ifelse(players_original_choice == winning_door,

sample(losing_doors, 1),

setdiff(losing_doors, players_original_choice))

does_player_switch <- i

players_final_choice <- ifelse(does_player_switch,

setdiff(doors, c(door_open, players_original_choice)),

players_original_choice)

}All the code is the same as in the previous chunks, with the exception of the does_player_switch object, which now takes the values of i. This value will be either TRUE or FALSE, depending on the iteration. The final bit of code that needs to be inside of the loop records whether the player switches and whether they win, and writes this into the monty_df object:

monty_df_i <- data.frame(

switched = does_player_switch,

won = players_final_choice == winning_door

)

monty_df <- rbind.data.frame(monty_df_i, monty_df)Full code

The full code looks like this:

n_iter <- 1000

switch_choice <- rep(c(TRUE, FALSE), each = n_iter/2)

doors <- c(1,2,3)

monty_df = NULL

for (i in switch_choice) {

winning_door <- sample(doors, 1)

players_original_choice <- sample(doors, 1)

losing_doors <- setdiff(doors, winning_door)

door_open <- ifelse(players_original_choice == winning_door,

sample(losing_doors, 1),

setdiff(losing_doors, players_original_choice))

does_player_switch <- i

players_final_choice <- ifelse(does_player_switch,

setdiff(doors, c(door_open, players_original_choice)),

players_original_choice)

monty_df_i <- data.frame(

switched = does_player_switch,

won = players_final_choice == winning_door

)

monty_df <- rbind.data.frame(monty_df_i, monty_df)

}Let’s have a look at the results:

monty_df %>%

dplyr::mutate(

switched = factor(switched, levels = c(TRUE, FALSE), labels = c("Switched", "Did not switch")),

won = factor(won, levels = c(TRUE, FALSE), labels = c("Won ", "Lost "))

) %>%

dplyr::group_by(switched, won) %>%

dplyr::summarise(n = n(), perc = n / (nrow(.)/2) * 100) %>%

ggplot2::ggplot(., aes(x = switched, y = perc, fill = won)) +

geom_col(position = position_dodge(width = 0.5), width = 0.3, alpha = .90) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#172541","#e2ad00")) +

labs(x = "\nDid the player switch their choice?", fill = "Did the \nplayer win? ", y = "Percent (%)\n") +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0,100)) +

theme_minimal()

Out of 1000 rounds, the player won about 66% of the time if they changed their choice, and only about 33% of the time if they sticked with their original choice. So yes, it is indeed to our advantage to always switch our choice.

As an aside, I should probably add that there are certainly more efficient ways of simulating this, but I find explicit for loops helpful for learning about coding because of how transparent they are. The execution time goes sky high as you increase the number of iterations, but that’s a puzzle for another day.

Footnotes

Which is pretty much never, unless you’re taking an introductory class in probability or re-watching Brooklyn 99 for the millionth time (which, given that you’re sitting here reading a post about a stats problem, you’re probably watching all by yourself, so there’s not anyone to wow anyway).↩︎

Again… never happens in real life.↩︎

In this case, either one and only one of the doors can be opened by the host in a single round, which is why this counts as a one sequence instead of two.↩︎